Metamorphosis – From LGOC NS bus to London United ‘Diddler’ trolleybus!

Metamorphosis – From LGOC NS bus to London United ‘Diddler’ trolleybus!

The evolution of bus design is a fascinating subject and probably happened faster in the 1929-1939 period, than in any other period. With London Transport, for example, one only has to compare London Transport’s 1929 ST1139, which had vestiges of a piano-front body, plus an open staircase and petrol engine, with its 1939 RT1, sleek and streamlined body and, out of sight, flexibly-mounted diesel engines, automatic brake-adjusters and automatic chassis lubrication!

One interesting example of evolution was the case of the 60 London United A1 and A2 class of trolleybus, commonly known as ‘Diddlers’.

These vehicles had their genesis in the LGOC NS class of bus, in its final form, with pneumatic tyres, enclosed driver’s cab and enclosed top deck.

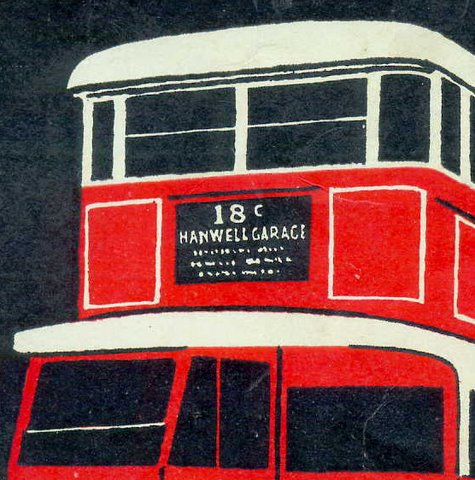

NS bus front - Note roof peak, centre upstairs window, with curved corner windows either side.

Copyright: M Dryhurst

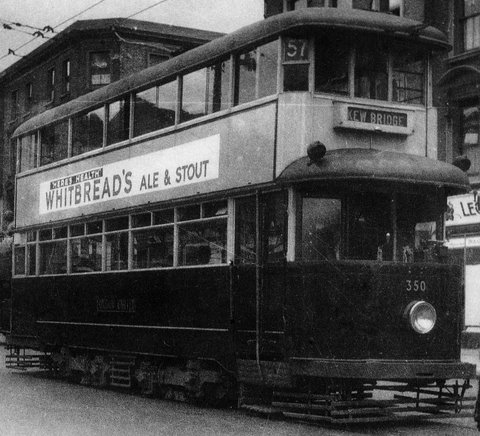

In 1927, Metropolitan Electric Tramways (MET), part of the ‘Combine’, was in need of some more modern trams and LGOC Chiswick-built experimental 350 was the result, nicknamed ‘Poppy’ after its distinctive upholstery. It was not followed through, but was sold to LUT. The tram remained unique, ploughing a lonely furrow on only two routes, finally going to an early grave by London Transport, in 1935. From the photo, however, a likeness with the NS front can be seen. Roof peak, centre upstairs window, with curved corner windows either side. Note the route number placed at the corner of the tram.

Copyright: Unknown

In 1929, MET decided that it needed some modern cars for high-speed work in West and North-West London and produced three distinct experimental types, the last one of which was ‘Cissie’, the forerunner of the famous 100 ‘Feltham’ class of trams, going into service in 1931. An ultra-modern, indeed stylish, car, it, and its sisters, still incorporated the NS/’Poppy’ front look, the production Felthams, even following ‘Poppy’s’ corner route number box! Ninety of the 100 went to Leeds around 1950, the last being retired in 1959. ‘Cissie’ went to Sunderland, its centre-entrance design rendering it incapable of being modified for ‘plough’ fitment. It now resides at Crich.

Preserved ‘Metropolitan’ Feltham Tram 355 at the London Transport Museum.

Copyright: John Bennett

The Union Construction & Finance Company (UCC), a somewhat mysterious, and, for the most part, moribund arm of the ‘Combine’, built the ‘Feltham’ trams, then built 60 ‘Diddlers’ for LUT. These were to replace the greatly loss-making and worn-out trams and track between Wimbledon and the Kingston/Tolworth/Hampton Court area. These trolleybuses were built in 1931 and externally bore a remarkable frontal resemblance to the Feltham tramcars! Peak on roof, centre upstairs window, curved windows either side, dome above cab, and, most bizarrely of all, later being given a centre headlamp on the front ‘radiator’ panel!

Thus, more than any other type, these trolleybuses could, on their looks, be called ‘trackless trams’! Despite their bodies being heavily rebuilt and modified during their first year in service, partly through frailty, they then somehow soldiered on until 1948/49 and their replacement by Q1 trolleybuses, not a moment too soon!

LUT 6 Class A1 at surviving tram stop in Kingston, with Class A2 37 heading in the opposite

direction. Note the awkward windscreen split which interfered with the driver's vision, until

the windscreen area was pulled in to widen it.

The two 'drums' on the roof are radio interference suppressors.

Copyright: AEC

I have included a link to a You Tube film clip that shows the strange windscreen setup and, later, shows a 'Diddler' and 'Feltham' together in Fulwell Depot, where they both resided. You Tube Clip

Chris Hebbron

11/2011

21/11/11 - 09:32

Thanks, Chris for this interesting insight into this period of change. I agree that the transition between NS and RT was remarkable, but not dissimilar to the changes taking place elsewhere in the UK (and sometimes earlier than in London). For fear of inciting hate mail from London readers, the strange Diddlers and superb Felthams were, in my opinion, one of the few occasions when London actually led the way in design, and all this was down to the UCC, MET and LUT. Had LCC or even LT been involved in the design of these vehicles, I suspect the results would have been much less inspiring and "safe". London lost a massive advantage when the decision was made to scrap the trams soon after the Felthams were built. Had they become the spearhead for modernisation, London could still have a extensive system where scale and fleet size would have given UK manufacturers a chance to compete worldwide and we wouldn't have to keep buying foreign. The RT's were fine buses, but they lacked real design flair and were simply a very refined version of what was commonplace in the provinces. It begs the question - what would UCC have built had they been around in 1939?

Paul Haywood

21/11/11 - 16:06

I joined London Transport in a clerical capacity from school in 1960, and found it to be very much a parallel universe. It was an inward looking organisation in many ways, and much of the claims made for it, such as the nonsense propagated about the overrated Routemaster, were indicative of the parochial naval gazing of wholly Metropolitan minds. Having said all that, I cannot agree that the RTs " lacked real design flair and were simply a very refined version of what was commonplace in the provinces". When the RT was designed in 1938/39, the concept of a bus with a large, lightly stressed, flexibly mounted engine, full air operation of brakes and preselective gearbox, and a jig built body of modern, high specification, the whole being readily accessible for maintenance, was certainly not commonplace in the provinces. The largest oil engine available elsewhere in Britain at that time was the 9 litre Albion, and although flexible engine mountings had been used successfully by Daimler and Dennis, and air braking had been employed on trolleybuses, no other bus than the RT combined all the features listed above in one design. It was a pioneering achievement that set the standard for the postwar double decker.

Roger Cox

22/11/11 - 07:20

Trams were doomed, nationally, by the conclusions of a Royal Commission, which reported, in 1930, that no new tram systems should be built and that existing systems should be abandoned progressively. (A side issue was the Tramways Act of 1870, which held tram operators responsible, not only for the track maintenance, and the road up to 18” either side; and track was getting tired). This report coloured political and operators’ opinion and set the scene for wholesale tram abandonment, with conversion to trolleybuses in some cases. It was a method of exploiting the only part-worn tramway overhead infrastructure and catering for 1930’s suburban expansion, with more flexibility, both in the street and route variation/extension. Thus, at the moment when some of the finest trams were starting to come on-stream to replace primitive turn-of-the century first-generation examples, the tap started to turn off!

Although the 1932 ‘Bluebird’ (LCC’s No.1, later LT’s No.1 & Leeds 301) was stylish, compared with the average E1-type LCC tram, it was not the design icon the Felthams were. Nevertheless, it was thoroughly modern and intended to be the first of a new breed of LCC tram. Also, the Tram/Trolleybus Division of newly-formed London Transport, under virtually the old LCC team, and with great autonomy, produced some really innovative and attractive trolleybuses, based on the slightly less attractive LUT’s No. 61. 70-seaters, silent and with blistering acceleration & deceleration, the tram seemed, by comparison, antedeluvian to the public.

Non-design innovation brought, in 1937, some of the world’s first monocoque-construction (trolley)buses, almost twenty years ahead of the Routemaster, then, buswise, the UK’s first rear-engine’d bus, the CR.

One of the greatest hindrances for ‘The Combine’ and London Transport was the Metropolitan Police, which stifled much of what was commonplace elsewhere, but they considered innovative, even foolhardy. Solid tyres, covered top decks, drivers open to the elements, open staircases, all permitted later than in the provinces, despite fierce argument.

I hold no great brief for London Transport, but its achievements in the 6-year 1933-1939 period were amazing. 'Welding' all the tram companies together, purchasing all the London Independents and integrating buses/routes, introducing the 1935-1940 New Works Programme. None of this was the lot of any public transport organisation throughout the UK.

The sad thing about the demise of trams was that the last operators scrapped their systems at the very point at which it was becoming obvious that there was a case for keeping them, such was the traffic congestion, especially those who had had routes on reserved track.

Incidentally, Roger, the jig-built body idea for the RT’s was a post-war idea, brought about by LPTB’s experience of building Halifax bombers at Aldenham during the

war. It delayed the RT’s re-introduction by around a year, making a difficult situation far worse.

Chris Hebbron

22/11/11 - 07:21

You're right, Roger with regard to the mechanical specification of the RT, but that was mainly for the convenience of LT's maintenance regime, and not for the benefit of the passenger. The RT was still a front-engined, rear entrance, half-cab bus being, as I suggested, a refined version of all other provincial buses of the time. What UCC did was to mould break, but the RT simply kept with tradition and ultimately led to the Routemaster which, as you suggest, was hyped beyond reason. Again, another opportunity to move forward was lost by LT.

Paul Haywood

22/11/11 - 12:32

Thank you Chris for your knowledgeable and thorough response to my somewhat over-egged and irrational (late-night) ramblings. You are quite right in everything you say, particularly regarding the Royal Commission on the future of tramways. However, many cities refused to follow this report and went ahead with tramway modernisation, but we all know the outcome. Had London also refused to accept the report, and set a precedent with a large fleet of Felthams and Bluebirds (and Baby-Felthams for the non-trunk routes) - who knows what may have happened. Dare I suggest that AEC might then have spent more time developing the Q to compete with or match the trams? Then, Leyland, Daimler, Guy etc. would have got to work with their own versions. Staying with the status quo lost this country its technical know-how, trade and influence. For me, the RT and RM were status quo. Had LT had more influence on the development of the Atlantean instead of being committed to (lumbered with?) the Routemaster, heaven knows what might have happened. Sorry, gentlemen, I've turned an excellent Metamorphosis into a rambling Diatribe.

Paul Haywood

22/11/11 - 15:46

Paul, Chris H & Roger. All three of you made both valid and accurate remarks but, as ever, the story is for ever labyrinthine. As an admitted AEC man, but one who has also driven them, no sensible person can gainsay the quality of the RT or RM. Unfortunately the RM suffered from McMillan disease. "Events, dear boy, events" overtook AEC and left them in the R&D gutter - never to really recover. The Atlantean was the way forward. Regrettably it took until the 1972 AN68 before it achieved it's potential. It then became a superb vehicle and was succeeded by another superb vehicle, the Atlantean/VRT cross, the Olympian. Unfortunately, the common cry for British industry is that we come up with good designs and never follow through with efficient production or quality of finish. Equally common has been the Japanese, or even Americans, nicking designs and them doing it better - although the Americans had reliable rear engined buses in the '30s. Would that those who can were left to do their jobs without ignorant outside interference - especially by politicians.

David Oldfield

22/11/11 - 18:44

It appears from our lively discussions that I am not alone in thinking that LPTB/LTE succeeded with the RT as much by accident as by design. I accept your point, Paul, that the Chiswick led motivation behind the "big engine" and other features of the RT concept was based on engineering and maintenance costings rather that passenger comfort. It just happened that the two things coincided. Much of LT's post war thinking on bus design was dictated by the Aldenham overhaul method that required buses to be taken apart and reassembled like Meccano. The Routemaster, like the RT, was conceived on these principles, with integral construction being adopted to save weight and sub frames being used to allow even greater application of specialised reconditioning tracks within the works. LT buses went through Aldenham about every five years, and emerged as virtually new vehicles. The extended service life of the RM accrued entirely from this extremely costly maintenance regime. The Northern General Routemasters, which lacked the luxury of Aldenham overhauls, had a service life of some 15 years, on a par with other contemporary 'deckers which had a lower first cost. As another example of LT's myopic view of the transport world, when it finally decided to evaluate rear engined double deckers, it bought 50 Atlanteans, and just 8 Fleetlines. Prejudgment, or what?I entirely agree with your sentiments, David, about British engineering achievements. We have done some brilliant things in the past and could again. It has been said that the only original Japanese idea is the Yagi antenna. The Japanese succeeded by taking promising ideas from elsewhere and re-engineering them for efficient mass production. Sadly, the City dominated objective of quick returns for shareholders, and the rise of private equity outfits and hedge funds set on buying up and asset stripping businesses whose share prices suffer a fall, do not offer much hope for the future. Germany does not allow this free for all, and its economy is much the better for it.

Roger Cox

09/12/11 - 08:38

One of the problems which London Transport had to contend with, from the early 1960’s, was its transfer from the BTC to local political control by the Greater London Council. PTA’s elsewhere have always seemed to do a fairly good job of co-ordination a multiplicity of bus companies, timetables etc, but the GLC’s political influence was at best negative and, at worst, almost malign. This meant that cheap transport solutions were sought and a price inevitably paid. When ‘Red’ Ken Livingstone, an ultra-leftist, took over, in 1981, he slashed bus and tube fares (‘Fares Fair’) to outrageously low levels, which made the organisation a pauper and resulted in an inevitable slowing down of investment in both vehicles/trains and infrastructure, which has taken decades to recover from. His fighting with Margaret Thatcher, IMHO, took his eye off the ball. With such an atmosphere, the GLC was abolished. Interestingly, under the Greater London Authority (GLA), with its directly-elected mayor, Livingstone, then Boris, controlling a London Assembly of local authorities, a very positive attitude towards London’s transport infrastructure has emerged, although the PPP arrangement for tube maintenance has had a rough ride. I do have some reservations about TfL’s franchising, though, but this whole issue also covers the railways and even the subsidy of certain bus routes by local councils! And it seems to me that a disproportionate sum of money is being given to London at the expense of the rest of the nation. We all know about the Law of Unintended Consequences and bus de-regulation was a case in point. To going from two bus groups to full nationalisation, then deregulation and a multiplicity of new companies, then down to Arriva, First, Go-Ahead & Stagecoach, we seem to have come almost the full circle! But all this is another story! We are where we are and longing for the past is pointless!

Chris Hebbron

Comments regarding the above are more than welcome please get in touch via the 'Contact Page' or by email at obp-admin@nwframpton.com

If you have a bus related article that you would like to appear on this site please get in touch via the 'Contact Page' or by email at obp-admin@nwframpton.com

All rights to the design and layout of this website are reserved

Old Bus Photos from Saturday 25th April 2009 to Wednesday 3rd January 2024